Pimachiowin Aki: The Land That Gives Life and Sparked Change

Prepared in collaboration with Pimachiowin Aki (pimaki.org)

Pimachiowin Aki, “The Land That Gives Life” in Anishinaabemowin (the Ojibwe language), is a living cultural landscape. Filled with an abundance of rivers, wetlands, lakes, and forests, it supports an abundance of wildlife, fish, birds and plants – proving the land’s name appropriate. Located in the boreal forest, Pimachiowin Aki is Canada’s first and only mixed cultural and natural UNESCO World Heritage site.

Pimachiowin Aki is an exceptional example of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan, or “keeping the land”, a cultural tradition of respecting all life forms and maintaining harmonious relations with others. To this day, First Nation communities within Pimachiowin Aki provide education about the land and culture through Indigenous knowledge programs. As leaders and educators, they provide training and lead and support scientific research to ensure that the world knows and respects the wonders of the land and people of Pimachiowin Aki.

The journey that Pimachiowin Aki embarked on to become a UNESCO World Heritage site is a testament to the importance of Indigenous leadership and knowledge in the effort to protect and restore nature.

The journey to becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) aims to provide peace through international cooperation in education, the sciences and culture. Their mission is to strengthen bonds among nations by promoting cultural heritage and equal dignity of all cultures.

The journey to becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site was 16 years in the making for Pimachiowin Aki, starting back in 2002.

- 2002: Five Indigenous Ojibwe communities, Little Grand Rapids, Pauingassi, Bloodvein, Poplar River and Pikangikum, meet to discuss their shared interests in protecting their ancestral land and way of life. They sign an Accord, committing them to land management planning and the creation of a linked network of protected areas within the boreal forests of northwestern Ontario and eastern Manitoba. The governments of Manitoba and Ontario recognize the value of adjacent wilderness parks in the area and add them to the evolving protected areas network.

- 2004: Pimachiowin Aki is added to the shortlist of 10 potential UNESCO sites after a review of 125 sites across Canada.

- 2006: The First Nations are joined by the governments of Manitoba and Ontario to form Pimachiowin Aki Corporation. With this partnership, they work towards a shared goal of designating Pimachiowin Aki a World Heritage site.

- 2012: A nomination bid is submitted by Canada to UNESCO on behalf of Pimachiowin Aki.

- 2018: Pimachiowin Aki officially becomes a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Pimachiowin Aki is the first and only mixed site of the 20 UNESCO sites in Canada. As a mixed site, it is recognized for both its cultural and natural values. It also became the first World Heritage site in the province of Manitoba.

Pimachiowin Aki set forth a change in how UNESCO assesses mixed heritage sites due to the unique combination of cultural and natural values. Not only was it a great example of Indigenous leadership in conservation, but also the leadership of Canada’s First Nations in the journey to reconciliation. With a deeper understanding of nature-culture connections, Advisory Bodies to the World Heritage Committee now collaborate to evaluate potential UNESCO mixed sites.

Did you know?

UNESCO World Heritage sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet one out of the ten outlined criteria to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

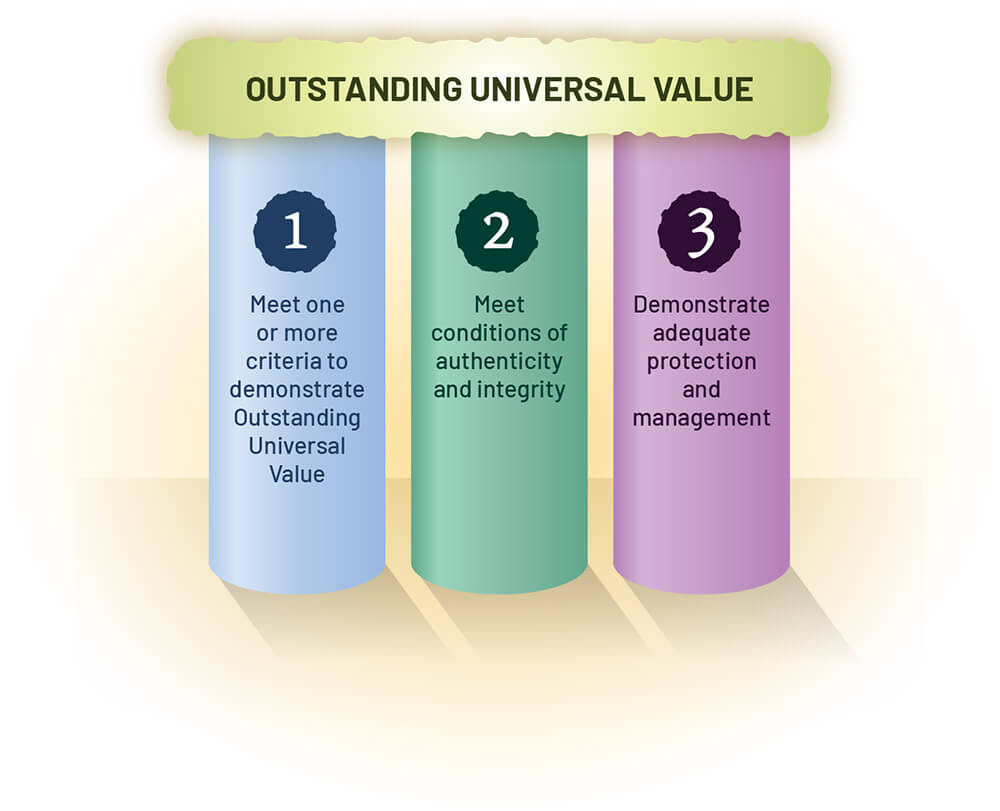

1. UNESCO World Heritages sites must demonstrate “Outstanding Universal Value”. Pimachiowin Aki met three of the criteria for selection:

- Criteria III: Is a unique or exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization that is living or has disappeared. Anishinaabeg care for the land today, as they have for over 7,000 years. They are guided by the cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan (keeping the land).

- Criteria VI: Is associated with events, living traditions, ideas, beliefs, or artistic or literary works of outstanding significance. The sacred responsibility and cultural tradition of Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan is sustained by systems of customary governance, and vibrant oral traditions.

- Criteria IX: Shows outstanding examples of ongoing ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of ecosystems and communities of plants and animals. The ecosystems in the boreal forest of Pimachiowin Aki are incredibly diverse, with rivers, lakes, wetlands, plants and wildlife. This supports the natural flow of life, including migration, reproduction, predator-prey relationships, and sustainable fishing, hunting, and trapping. The site is home to approximately 400 mammal, bird, amphibian, reptile, and fish species—including at-risk species.

2. Meets conditions of authenticity and integrity. Pimachiowin Aki is home to a flourishing boreal forest and ancient culture that still thrives today.

3. Demonstrates adequate protection and management. The Pimachiowin Aki partnership safeguards the site through Anishinaabe customary governance grounded in Ji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan, contemporary provincial government law and policy, mutual respect and collaboration.

The Guardians program

Like the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, Pimachiowin Aki’s Guardians are the eyes and ears of the lands and waters and help accomplish stewardship goals. The program offers opportunities for jobs, lowers crime rates, and improves public health. The program aims to inspire youth, offering a connection to their language and culture.

The Guardians observe, record, and report on the health of ecosystems and cultural sites and share their knowledge or concerns with communities, visitors, stakeholders, and partners. Their activities include:

- Observe activities or changes of note, such as wasteful hunting or the spread of an invasive plant, and respond accordingly.

- Talk to visitors and community members to raise awareness of the need to protect Pimachiowin Aki.

- Draw on land-based knowledge to monitor indicators of the cultural landscape and ecosystem health.

- Educate the public about things they can do to be good stewards of the land.

- Report information, such as a wildfire or illegal activity, to relevant authorities.

- Care for cultural sites, such as removing litter and making offerings.

- Work with knowledge-holders to establish agreements on how the monitoring results can be stored and used.

The land and culture that continue to give

Nature Canada is committed to supporting and promoting Indigenous-led conservation, recognizing the importance of partnership for the sake of wilderness and landscape. Pimachiowin Aki’s history is a testament to the determination of the First Nations, who worked together to defend the land and a stunning example of how Indigenous-led conservation is critical to Canada’s vision for protected and restored nature.

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) are great examples of long-term commitments to Indigenous-led conservation. IPCAs are lands and waters where Indigenous governments have the primary role in protecting and conserving ecosystems. They do so through Indigenous laws, governance and knowledge systems. By crafting various partnerships with environmental NGOs and Crown governments or others, Indigenous governments pave the way towards achieving conservation with respect and care for both land and culture.

What’s next?

To learn more and stay up to date on Pimachiowin Aki, subscribe to their newsletter and follow them on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

To learn more about how Nature Canada is supporting and promoting Indigenous-led conservation efforts subscribe to our newsletter!

— Excerpt from Nature Canada’s RECONCILIATION PRINCIPLES FOR OUR WORK WITH INDIGENOUS PEOPLES