Announcing the 2025 Charles Labatiuk Scholarship Award Winner: Brandon Weigand

This guest blog was written by Brandon Weigand, the 2025 Charles Labatiuk Scholarship Award Winner. Brandon is a graduate student in the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia.

Though we don’t often realize it, the animals living in our cities are some of the most tenacious on the planet. They must continuously adapt to our demands, negotiating the perils of the urban matrix to feed and forage, their lives evolving in constant synchrony with the very environments that sustain and endanger them. And yet, despite all their ingenuity, urban species are often reviled or ignored, sometimes even absent in the collective mythos that draws conservationists toward protecting wildlife in the first place. Love them or hate them, they share in the same delicate dance between survival and adaptation that all animals do, ourselves included.

Author Brandon Weigand with one of his water depth and atmospheric monitoring instruments in Vancouver’s Everett Crowley Park.

We often overlook the animals that move among us, yet our presence means everything to them. Faced with countless hurdles unique to the urban environment, the wildlife here have carved out ingenious toolkits, evolving clever adaptations to the pressures of our own design. Consider one of the most emblematic forms of urban wildlife: pigeons. These birds can memorize the safest routes through crowded streets, timing their movements to minimize risk while maximizing reward. They can even recognize individual humans, distinguishing between those who feed them and those who might threaten them. Many other species, such as raccoons, crows, coyotes and squirrels, possess traits that have made them remarkably successful: unflinching curiosity, impressive risk-taking, the intelligence to learn and remember, and the adaptive bravery to turn the scraps of our world into opportunity. These qualities have made these animals not just survivors, but blueprints for what it means to persist in an increasingly urbanized world.

Brandon Weigand teaches others to perform aquatic insect collections at one of Vancouver’s most beloved pond sites, Jericho Beach Park.

Still, I’ve often heard people dismiss urban staples like pigeons as “flying rats,” a phrase that slurs what is, in truth, an extraordinary survival story. But it is their opportunism – the strategic flexibility that allows them to thrive alongside us – that seems to fuel the broader indifference I’ve seen toward urban wildlife as a whole, casting many species into obscurity through our collective irritation, or through our discomfort in recognizing that scavenging can actually be a form of calculated ingenuity. Carl Jung once said the darker, suppressed aspects of human psychology are revealed in the ways we treat animals. I often wonder if this is the case with our so-called “flying rats.” Pigeons lead remarkable lives, as do other urban creatures like sparrows, raccoons, opossums and, of course, rats. Yet we’re quick to dismiss them as a pestilence or nuisance, sometimes fearing or even hating them. Certainly, some creatures like bats, insects, and snakes can harbour real dangers, and caution is wise. But many of these animals are simply fellow survivors, forced to adapt in landscapes we claimed from them and remade for ourselves. If we could learn to notice them with curiosity instead of contempt, we might find their resourcefulness rather inspiring.

And perhaps the very phrase “flying rats” exposes a deeper conundrum about conservation itself. If we struggle to see the resilience of pigeons or the resourcefulness of raccoons, how can we hope to nurture an honest appreciation for species beyond our concrete borders? Endangered animals like rhinos and gorillas unquestionably deserve protection, but why not extend some of that wild imagination and environmental ethic to the everyday creatures that live alongside us? Is it a question of rarity or resources? Or have we inadvertently narrowed conservation to a paradigm that favors the distant while quietly dismissing the familiar?

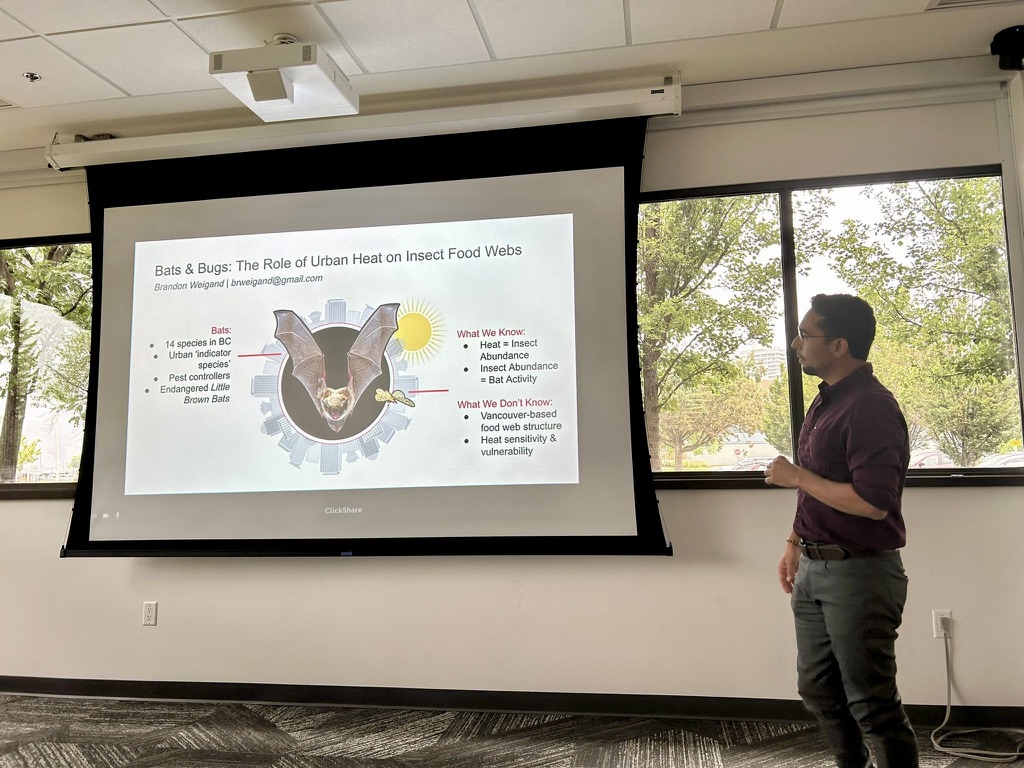

Brandon Weigand delivering a presentation on urban heat and biodiversity to city stakeholders in Kelowna, BC.

“Urban” Does Not Mean “Secure”

The heart of my work lies not in providing definitive answers to these complex questions, but in adding nuance and perspective that might move the conversation forward. My aim is simple: to give urban wildlife the attention it deserves, not only for its resilience and adaptability, but for its intrinsic worth as part of our shared ecosystems. As biodiversity declines globally, I often wonder if the species in our cities might become our last bastion of nature preservation. To prepare for that possibility, we need to understand how urban inhabitants live, thrive and, too often, perish within these rapidly changing landscapes. As wetlands give way to pavement and climate extremes strain already-limited habitats, we are reminded that the wildlife closest to us can disappear as suddenly as the endangered species we fight to protect elsewhere.

I study the lives of one particularly vulnerable urban species: bats. Though often imagined as distant creatures of caves and forests, many bat species find refuge in cities, making their roosts in buildings and homes. Far from being distant phantoms, they are actually some of our nearest neighbors, sometimes more common than other forms of urban wildlife. In fact, if you glimpse a fleeting silhouette after sunset in your city, there’s a good chance it’s a bat. They are masters of evasion, slipping beyond our awareness through their nocturnal habits. Emerging at dusk and vanishing by dawn, they take to the skies with incredible efficiency. Just one bat can consume thousands of pest insects in an evening.

Brandon Weigand assisting the Wildlife Society of Canada’s efforts to monitor threatened bat species in Vancouver. He is holding a Yuma myotis, a common species found throughout the city.

Like pigeons, bats have carved out a special place within our cities, adapting well to the challenges we’ve afforded. But while pigeons endure disdain, bats carry a longstanding archetypal terror, one that too often overshadows their true evolutionary marvel. Bats are the only mammals to have evolved true flight, and the only ones to use echolocation to hunt, navigate, and communicate in the dark. Many bat species form thriving social communities, with dynamic family bonds, cooperative care, and layered hierarchies that mirror our own. Their intelligence allows them to learn, remember, and solve problems, while their aerial precision is unmatched in the animal kingdom, capable of maneuvers so breathtaking they would leave even Cirque du Soleil performers in awe.

And yet, bats remain reviled. Centuries of folklore have cast them as sinister predators, when in reality they are among our most cautious neighbours, skimming the night with a careful discretion intent on avoiding us entirely. Like many forms of urban wildlife, they are opportunists, but theirs is particularly unique, thriving in the niches our nightly lives provide. While we sleep, bats inherit a quieter city, the street-lit skies theirs to freely navigate, their voices carried in ultrasonic cries we cannot hear. If pigeons are a blueprint for urban survival, bats may well be its triumph. Still, if there is one creature that personifies our struggle to embrace urban wildlife, it is the bat.

It is that very difficulty that makes their future all the more fragile. Vancouver’s little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) have, for now, withstood the looming arrival of White-nose Syndrome, a devastating fungal disease that has decimated more than 90% of colonies across Eastern North America. Whether through luck or some yet-unknown factor, they are holding on—but I don’t expect this will last. The precursors of White-nose have already been detected uncomfortably close to the city, and it may only be a matter of time before it reaches our Western shores. In that narrow window of time lies a special responsibility: to study how Vancouver’s bats live, so we are not left only to study how they die.

Realizing Goals

For me, studying urban bat ecology is as much about ensuring their survival as it is about inspiring others to value what we still have. To do this, we need to know how bats navigate the city, what they eat, and how they prioritize decisions under changing conditions. Food webs can vary greatly between cities, and in Vancouver, the connections between insect prey availability and insectivore survival remain largely a mystery. What we do know is that urban life offers both risks and opportunities, shaping when, where, and how these animals can find sustenance. When our green and blue spaces are disrupted or lost, whether by habitat degradation, contamination, or increasing climate extremes, bats and other aerial insectivores may be forced to travel farther, compete harder, and expend energy they can hardly afford, especially during the breeding season. My research explores these pressures in tandem, emphasizing that the fate of urban wildlife depends not only on their capacity to adapt, but also on the integrity of our shared environments.

But this is only the first stage of my research. The 2025 summer field season was a chance to refine methods and glimpse the connections at play, but next year I hope to widen the lens considerably. As I enter my PhD program, I also want to incorporate more holistic measures to understand how both bats and other threatened insectivores, like barn swallows, maneuver around threats like heat islands and how they select prey across time and space. The Charles Labatiuk Scholarship is a pivotal foundation for this work and many other efforts, equipping my research team with the tools we’ve long envisioned. With its support, my team at UBC will help develop a network of cutting-edge sensors to track insectivorous species across Vancouver, linking food webs, habitat health, and movement ecology into a fuller picture of how wildlife truly lives in our city.

Brandon Weigand venturing into the pond margins of Vancouver’s Trout Lake to retrieve field equipment.

Dispelling the myths surrounding urban wildlife is also a priority, which means making their existence visible to the public. To that end, I lead bat walks through Vancouver’s parks, collaborate with the Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, and volunteer with the Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada to investigate probiotic resistance to White-nose Syndrome. One effort already underway is a passion project to restore UBC’s severely diminished barn swallow populations, involving multiple stakeholders, partners, and community members in developing tangible, hands-on opportunities to learn more about the city’s threatened fauna. These efforts are about creating lasting encounters; moments when people can see, hear, or imagine the lives of animals that often slip past us unnoticed. From these efforts, I hope to leave behind not just data, but a shift in perspective, a recognition that the animals sharing our streets and skies are part of the same conservation story as those in far-off places. By making their presence visible, I hope to teach others that protecting the familiar is inseparable from protecting the rare, not because the familiar is any less remarkable, but because it is surprisingly easy to grow indifferent to their wonders.

And perhaps that is central to discussing honest conservation. If pigeons remind us that ingenuity happens in plain sight, and bats challenge us to appreciate what we fear, then instead of defining the boundaries of conservation, maybe we should work to blur them. Maybe we could learn to simply look around us, to see opportunity where others see nuisance, to recognize resourcefulness where others see intrusion, to contemplate the unspoken ire in phrases like “flying rats” when we see pigeons along the street. Valuing the overlooked and nearby need not diminish the distant and extraordinary, but instead situate them within a richer story of resilience and survival. Urban species may not fit the traditional mythos of wildness, but perhaps that is exactly why they matter. They remind us that survival is not only happening elsewhere, but also here, quietly, in the periphery of our daily lives.

You can read Brandon’s essay below:

The Place Where Wilderness Never Left

A few days after moving into my new home, while sitting with my partner on the back porch, a small shadow flew across my face. I looked up and met eyes with a beautiful barn swallow perched atop her nest. I hadn’t noticed it before, but she had hollowed out a section of the under-roof, cleverly furnishing it into an elegantly disheveled mud dwelling. She was beautiful. Vivid crimson feathers framed her neck and face, contrasting with her black-blue iridescent plumage, which shimmered in the afternoon sun. Her beady eyes looked, at first, to reflect nervousness, but within them I also saw a calm stoicism, as though I was not the first inhabitant of the house to share such an exchange. I was hypnotized. After a few moments, she flew back out into the sunlight, whether out of fear or natal obligation I wasn’t sure. But that exchange was, thankfully, the first of many more to come.

Our continued relationship was personally serendipitous. At the time, I had just finished reading “The Trouble with Wilderness” by environmental historian William Cronon, where he passionately argued against the notion that civilization was inherently lesser than the wilderness that surrounded it. He argued thoroughly—and I believed him—that civilization and ‘untouched,’ ‘untainted’ wilderness were part of the same thing; that human-dominated landscapes were rather a unique expression of wilderness, sprung from the same precious earth. It was a radical concept, challenging many of my preconceived notions of what it meant to be “wild.”

This barn swallow exemplified Cronon’s principle. This was a creature displaying visceral, supposedly wild behaviors, yet within my physical reach. Here, in the depths of suburbia itself, was an animal that cared little for the anthropocentric definitions or the constraints on wilderness we humans seem to impose on it and other fauna, personifying the reality that we are no different, no less ‘wild’ than our animal kin. As seems apparent in the modern conservation paradigm, the sheer expansion of human development has and will continue to threaten animal species, and particularly those that sit on the fringes of civilization. This swallow, however, appeared completely unfazed, seemingly inattentive to such a reality, oblivious to the fact that many other native species, including other swallow species, were becoming threatened or worse. Indeed, she seemed to be thriving here, nestled peacefully amidst a raucous human environment.

Each morning I watched her dart skillfully between trees and rooftops, a streak of motion against the sky, as she collected food or nesting materials. Over time her nest, once unnoticed, became a focal point of fascination. I was taken by the way she had adapted so seamlessly to the human world, building her life above mine as though the lines between wild and domestic had never been drawn. Swallows, after all, have long lived alongside humans, nesting beneath barn eaves and bridge ledges, yet their quiet resilience often goes unseen. Her success was a testament to the flexibility of nature, a reminder that wildlife is not always distant or separate but embedded in our daily lives. I was reminded of this every time I peered up at the nest I accepted and embraced as a permanent fixture of my home. Well, our home.

And yet, her presence left me wondering. If she could persist amidst the noise and asphalt, why were so many others fading into extinction? Why do some species flourish at the edges of our world while others quietly vanish from it? In her silent way, the barn swallow gave shape to a question that has been stirring within urban conservation: what are the barriers that can and will prevent human and non-human lives from truly thriving — not apart, but in shared and mutually sustaining space?

That question has since become the wingbeat of my graduate work. I am now pursuing an MSc in urban ecology at the University of British Columbia, where I study the aquatic insect food webs that sustain urban wildlife in the Pacific Northwest. Mounting pressures from urban expansion, warming microclimates, and shifting hydrology are fracturing these systems, unraveling the delicate threads between insects and the many species that depend on them. And so, I spend my days knee-deep in urban pond margins and shaded wetlands, tracing how the most pressing hazards of city life – urban heat islands, freshwater drought, and rising development – ripple through these fragile webs, seeking to understand what allows insect communities to persist and what drives their collapse, so that the creatures who depend on them, swallows included, can continue to raise their young beneath our rooftops.

In following these threads, I hope to honour Cronon’s vision of cities not as places where nature ends and humanity begins, but as shared landscapes of belonging, where the humans and non-humans endure together as part of a single, true wilderness. I want to see cities not as barriers to biodiversity but as unexpected backbones for its preservation. My work aims to help reimagine how we practice conservation: drawing on ecological insight to confront present threats and anticipate those still to come, so that our urban landscapes might stand as resilient sanctuaries where our wild neighbours continue to inspire a lasting connection to the wilderness around us, just as one barn swallow once did for me.

Over time, she and her family grew less wary of my own, living as quiet cohabitants who shared in the rituals of home-making. Though we always stayed out of each other’s lives, staying just beyond each other’s reach, she certainly left a lasting mark on mine. To me, her nest became more than shelter but rather a lesson in coexistence, a reminder that wildlife is not something distant or apart, but here with us, in our cities, our backyards, under our roofs. A reminder that conservation is not only about protecting the remote and distant, but also about embracing the nature that exists right alongside us, in the places we call home.