Marine species at risk and the three loopholes in the Federal Species at Risk Act

What are species at risk?

Species at risk are any species that are in danger of disappearing from the wild, or in a geographic area. For example, there are some species that are globally secure but might be at risk of disappearing from Canada, like the spotted owl. There’s one known breeding pair left in the wilderness of B.C. but still a decent, yet declining, population in the U.S.

How are species at risk determined?

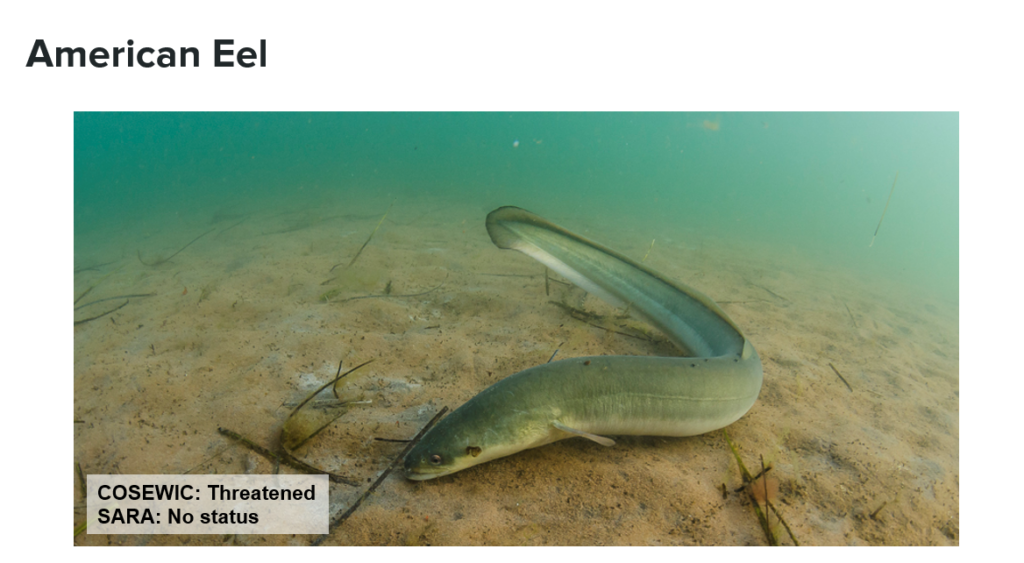

In Canada, we have an independent advisory panel that assesses which species are at risk of extinction in our country called the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). They determine if a species is extinct, extirpated, endangered, threatened, of special concern, not at risk, or if there is insufficient data to make the call. Knowing which species are at risk is the first crucial step in saving them. Once COSEWIC finds evidence of an at-risk species, they then send their recommendation to list it as such to the federal government, who ultimately decides whether or not to add the species to the legal list under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA).

What are the types of species at risk?

A species can be assessed as:

EXTINCT: A species that no longer exists.

EXTIRPATED: A species that no longer exists in the wild in Canada, but occurs elsewhere.

ENDANGERED: A species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

THREATENED: A species that is likely to become endangered if threats are not reversed.

SPECIAL CONCERN: A species with characteristics that make it particularly sensitive to human activities or natural events.

NOT AT RISK (NAR): A species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk.

DATA DEFICIENT (DD): A species for which there is insufficient scientific information to support a status designation.

A species’ COSEWIC status does not mean they receive legal protection. For a species to be legally protected under the federal law, in other words SARA, they must be added onto schedule 1 (the legal list) by the federal government. The federal government can decide whether or not to follow COSEWIC’s assessment to legally list, and therefore protect, the species.

How is wildlife in Canada doing?

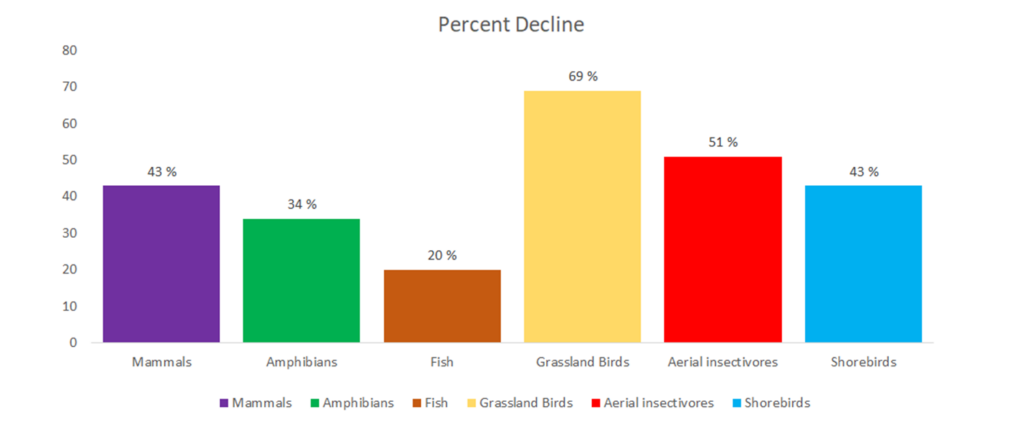

From 1970 to 2014, half of monitored wildlife species in Canada declined dramatically from 451 of 903.

Here are some examples of marine species at risk, as assessed by COSEWIC and the SARA.

The Species at Risk Act and its loopholes

The SARA’s purpose is to prevent wildlife species from becoming extinct and to support their recovery.

Under SARA it is an offense to:

- Kill, harm, harass, capture, take, possess, collect, buy, sell or trade an individual of a species listed in Schedule 1 of SARA as endangered, threatened or extirpated.

- Damage or destroy the residence of one or more individuals of a species listed in schedule one of SARA as endangered, threatened or extirpated (if a recovery strategy has recommended the reintroduction of that extirpated species).

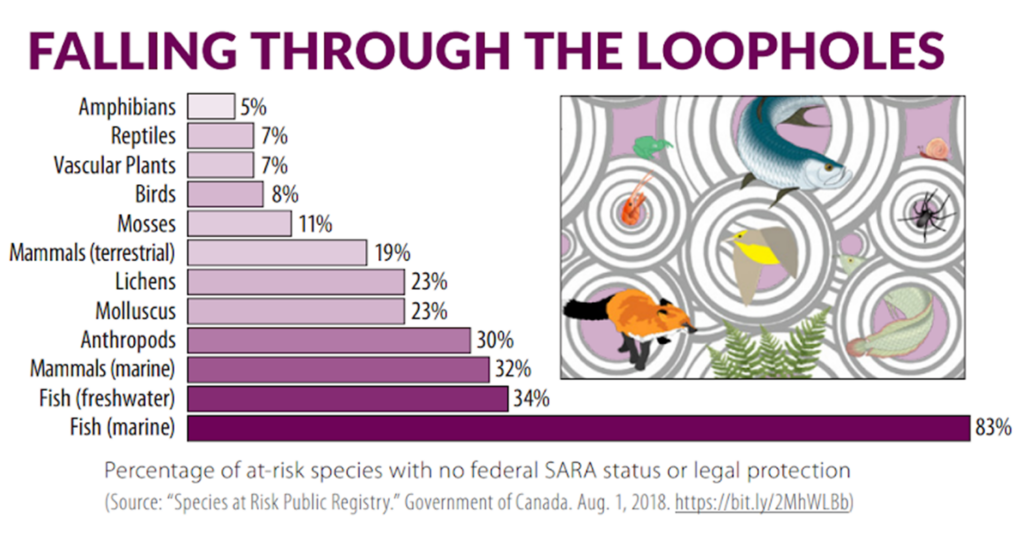

Unfortunately for struggling species, there are many loopholes that prevent the above protections. Many species at risk end up having no protection from being harmed and having their habitat destroyed.

Loophole #1: Only aquatic species, migratory birds, and species on federal land are automatically protected.

For terrestrial species at risk, protection depends on where they are located. Species living on non-federal land are not automatically protected. In Canada, there’s a lot of non-federal land— 59 percent nationally, and sometimes less in the provinces, like in B.C. where only 6 percent is federal.

This means that federal land, where automatic protections apply, are essentially just the following: airports, national parks, military bases and post offices.

All of the offences described above do not apply to terrestrial species, which are land-based creatures, on provincial land, which is the majority of the landbase. The result is that it’s entirely legal for endangered species like the whitebark pine tree to be cut down as long as they are not for example, in a national park. Sometimes, the law does protect species; Lake Louise ski resort was charged $2M for cutting down 38 trees in 2018. But meanwhile, on non-federal land across B.C., it’s entirely legal for logging companies to cut these trees down. And they do!

Marine species at risk SARA application

Luckily for marine species, the SARA does automatically apply to them since the marine environment is under federal jurisdiction. In theory, SARA makes it easier to protect marine species at risk but due to another loophole, many marine species do not get the protection they deserve.

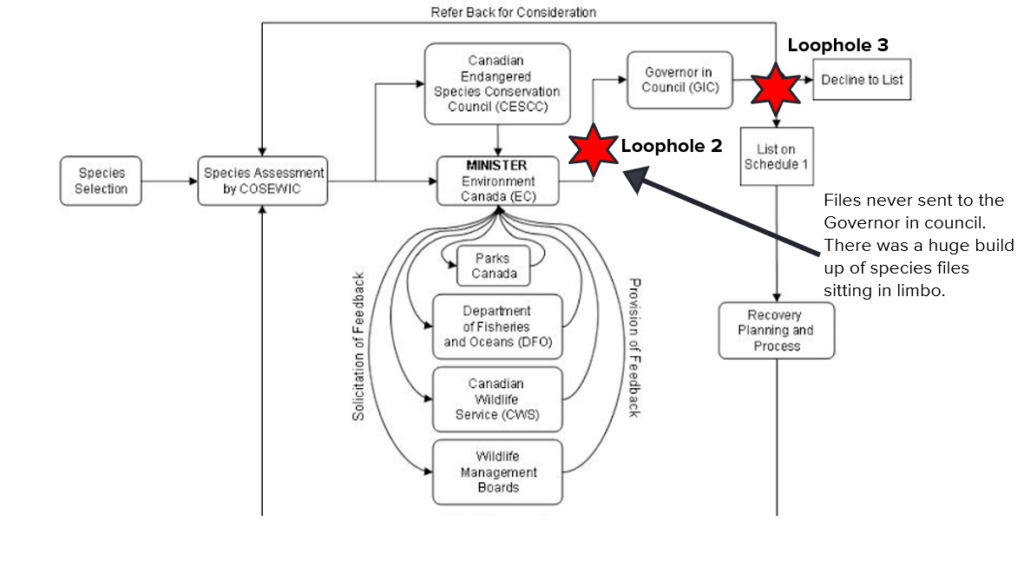

Loophole #2: Government can avoid making decisions on listing species.

Vague wording in the law has allowed the government to avoid making decisions altogether when it comes to officially listing species. Species that COSEWIC have found to be at risk sit in legal limbo for years, during which time their populations continue to decline. As they sit in this legal limbo they receive no protection from SARA. Nothing stops them from being harmed or having their habitat destroyed. Of the 172 marine species listed as at risk, 116 of them have no legal status and are sitting in this limbo—that’s 67 percent of marine listed species at risk receiving no protections from SARA.

Here’s how the process is supposed to work, according to the government’s Species At Risk Act:

- COSEWIC prepares a list of species it judges to require some form of protection and sends it to the federal environment minister.

- The minister has three months to agree or disagree with the assessment. If they think more analysis is required, the case is sent for further examination. Otherwise, they send the whole file for consultations after which a recommendation on whether or not to list the species is sent to the governor in council, which then has nine months to make a final decision. They can consider social and economic impacts (more on this later) in this decision.

- If the government doesn’t respect those deadlines, the species are supposed to be automatically added to the endangered species list.

Once COSEWIC passes the assessment to the minister, the minister has 90 days to issue a response statement. But after that point, once the minister passes the government’s recommendations to the federal cabinet, there’s no timeline for action. Before getting any kind of federal response, a species can be made to wait for years.

Under Stephen Harper’s government from 2005-2006, vague wording was used in the law to avoid taking actions to protect at-risk species. The issue wasn’t that the wildlife were outright rejected during Harper’s government—only three species got a definite “no.” The problem was that nearly 90 percent of species COSEWIC found to be at risk were never sent to the governor in council. They were instead placed in an administrative limbo, to be dealt with at a much later date.

Loophole #3: The federal cabinet can decide not to list a species based on socio-economic considerations

When it comes to federal protections, not all types of species are considered equally. Governments are more likely to list species as at risk who don’t necessarily receive automatic habitat protection on all land once listed (see Loophole #1), for example: amphibians, reptiles or vascular plants. Marine species are trickier from a socio-economic perspective. Their automatic protections under the SARA can impact various industries, like the fishing industry. For this reason, they are less likely to be added to the legal list.

Poor pocket moss, with a Canadian range limited to just a small area in Lynn Canyon of 249 hectares, is an easy decision to list. This is because there are slim chances logging or industry will go after it, especially if the habitat it’s found is on non-federal land.

Governments can state any social or economic reason when they decline to list a species at risk which can get in the way of science-based decision making. The porbeagle shark, for instance, wasn’t added to the legal list not because it wasn’t at-risk, but because the federal cabinet decided its protection could negatively affect the fishing industry.

Marine species lack protections under SARA

Studies show that species are less likely to be listed as threatened or endangered under SARA if they are the target of a commercial harvest, the most obvious example being the demise of the Atlantic cod. Startlingly, of the 172 at-risk marine species, 116 of them have no legal status and are sitting in limbo… that’s 67 percent of marine COSEWIC-listed species at risk.

Worse still, the more endangered the fish, the less likely it is to be listed. From 2003 to 2015, only 12 (19.3 percent) fish species were listed under SARA, including just three endangered species, and two threatened species. Most species—60 percent—are still awaiting a government decision.

Even once added to the legal list, marine species at risk aren’t necessarily protected from harm.

Even species that are listed by SARA, with mapped critical habitat, a recovery strategy, and within federal jurisdiction can be legally harmed. This is because the federal cabinet can decide to approve projects that have been found to harm species at risk based on socio-economic implications.

Case study: Trans mountain pipeline expansion (TMX) vs. Southern resident killer whales

Southern resident killer whales are endangered and legally listed under SARA. Their habitat is mapped, and a recovery strategy has been put in place. As a marine species, SARA automatically applies to them. So, one would think that when it was determined that TMX would have significant adverse effects on the whales, it would be halted.

This was not the case.

Under SARA the TMX would violate SARA this could have been the end of the project. Instead, the federal cabinet then decided the negative impacts to the whales were justified in the name of socio-economics.

The SARA can be a strong legislative tool if the federal government in power stops undermining it. In a very real way the SARA is as strong as the will of the government in power.

Four steps in the way forward

- Amend SARA. Strengthen the law by amending it so that the loopholes no longer exist. However, if the act were to be opened up for change, it must be ensured that the law is in no way amended to be ever weaker than it already is. Fear of this option doing more harm than good is the reason amending SARA has not been explored.

- Hold the government accountable. SARA can be strong if the government in power is. We have the power to vote people in and out, including cabinet members and members of parliament, who continue to undermine the act.

- Protects species below the federal level. All provinces and territories should enact standalone laws to protect all the species that fall through the cracks of the federal law. This would include protecting the habitat of all wildlife found on non-federal land.

- Work with First Nation communities to strengthen SARA. In addition, any new law or amendments to existing wildlife protection laws must be co-created with Indigenous Peoples and uphold UNDRIP. This is important so that sovereignty over traditional lands is built in from its inception.

Ultimately, species need time and space to recover. Sometimes that will require a sacrifice in the near term to save the species in the long term. In the case of Atlantic cod, if we had stronger regulations on harvest and had given them time to recover, perhaps their populations never would have collapsed in the first place.

Prioritizing the health of wildlife and wilderness will require a shift in why we make decisions and who benefits are made for. We should prioritize decisions that benefit ecosystems, and the species and human communities relying on them, rather than the industries that profit off them. Any politician that fails to prioritize this, should be held accountable and we can do that with our vote.