5 Ways to Decolonize Your Canoe Trip

This blog was written by Jocelyn Dockerty.

It has been around that time of year where some Canadians are celebrating our 150th birthday. Now, as someone trained to be a history teacher, I could write a whole lot to complicate that number 150. That’s not why I am writing this piece today though, but it is related.

Canadians need to decolonize themselves. This is becoming a more and more common thing to discuss today. It is in our social media feeds, in national headlines, and beginning to be discussed in schools. But what about in our canoes, during our paddling trips, in the outdoor adventure community? There definitely is much decolonization to be done within this community and many scholars are already discussing this.

For us, four women paddling through Quetico Provincial Park very soon, there are a few minor steps we are taking to engage in decolonization. I understand that I am a fortunate white lady writing this piece and it would be ideal to read how to decolonize your canoe trip from an Indigenous individual, but I do think it is important to share our experiences and how we are consciously trying to engage in decolonization. Below are minor steps that any Canadian tripper can take before they embark on a paddling trip. Of course, decolonization will need much more than these 5 steps, but they are a great starting point.

1. Know the Treaty Territory You are Paddling Through

We are all Treaty people. All human experiences in Canada are extremely connected to what was signed in our treaties. It is important to know them. So before you begin your next paddling trip, visit this awesome website Native-Land.ca and find the treaty territory you are in. You can then visit Canada’s Indigenous and Northern Affairs Website and print out the text of that very treaty. Find a Ziploc bag. Bring it on your trip and read it with the community of paddlers you are in. Read it again. Question it.

We are all Treaty people. All human experiences in Canada are extremely connected to what was signed in our treaties. It is important to know them. So before you begin your next paddling trip, visit this awesome website Native-Land.ca and find the treaty territory you are in. You can then visit Canada’s Indigenous and Northern Affairs Website and print out the text of that very treaty. Find a Ziploc bag. Bring it on your trip and read it with the community of paddlers you are in. Read it again. Question it.

We will be paddling through Treaty #3 Territory, which covers about 55,000 square miles from Thunder Bay to the north of Sioux Lookout, along the international border to the province of Manitoba. There are 28 First Nations communities within Treaty #3, the nearest being Lac La Croix First Nation.

Interestingly enough and not surprisingly, Quetico Provincial Park has a complicated relationship with the original peoples of this territory. Here is an excellent article that shares the story of one of the last Indigenous women to live in her traditional lands in Quetico. Click here to read the story. You can also read more about Quetico Provincial Park’s history with Lac La Croix First Nation from pages 27 to 29 in this report.

2. Know the Indigenous Language(s) of the Territory You Are In

English speaking Canadians get funny about learning languages. It is the privilege of being English speakers. You travel or live elsewhere and it is a simple reality that people are polyglots. Canadians need to jump that hurdle of unilingism and this does not only include French. Indigenous languages have been systematically threatened through Canada’s education system. This affects our recognition of Indigenous culture, ways of knowing, and presence in Canada today.

“Losing a language is a major setback for everyone, because along with the language, you will also lose all of the poems, the stories, the songs. And those things are of immense importance to all of us as human beings.”

—Anthony Aristar—

We need to learn our Indigenous languages. Begin by learning what the language of the territory you are paddling in is. Anishinaabemowin? Kanien:ke’ha? Cree? Halq’eméylem? After that, try learning some basic phrases, such as “Hello,” “My name is…,” or “Thank you.” It is respectful to do this when travelling to other nations. Canadians can begin to decolonize themselves by recognizing that when they are in Indigenous nations, it is also respectful to learn basic phrases.

The primary Indigenous language used in the territory that we will be paddling through is Anishinaabemowin. That being said, so many languages have been used in this territory due to its important trading history even before Europeans arrived.

Some members of our trip have gradually been learning Anishinaabemowin. An excellent literary resource is Talking Gookom’s Language. This book also includes a workbook and CD to practice phonetics. Ideally, connecting with humans is better but resources to teach and learn Indigenous languages are small, so there are not always classes in your community to learn your local Indigenous language.

3. Learn the Indigenous Names for the Territory You Are In

Ontario, Toronto, Quebec, Saskatchewan and so many other Canadian locations are rooted in Indigenous languages. For example, Kenora is the amalgamation of 3 different towns: Keewatin, Norman, and Rat Portage. Two of those three town names have Indigenous origins. Keewatin describes a north wind. Rat Portage is the English translation of Wauzhuskh Onigum meaning “portage to the country of the muskrat.”

Why on earth does it matter to learn this? By recognizing Indigenous history and influence to Canadian communities, we rebuild a narrative that demonstrates that Indigenous peoples were not passive actors in our history. Indigenous peoples were and are active in this land. Words matter.

Before you begin paddling, try to find the Indigenous name of the major rivers or lakes of your route. How can you do this? There are hundreds of Native Friendship Centers throughout Canada whether in metropolises such as Montreal or Toronto or in small towns such as Quesnel or Sioux Lookout. Many Native Friendship Centres employ Cultural and Language Coordinators or are in close connection to Elders. Email them. Ask for information. Even if they do not know their language, they may be able to direct you to people who do. It is important to not assume that just because someone is Indigenous, that they may be able to speak an Indigenous language. That assumption doesn’t really recognize structural reasons as to why many Indigenous peoples do not speak their languages (i.e. residential schools, lack of funding for Indigenous languages, generational gaps in knowledge of languages, etc.). So, begin the conversation and show that Indigenous history and languages matter to you.

Honestly, we are still in the process of learning this. There is much to learn and we are committed!

4. Learn Your Waterways

Click here for more information.

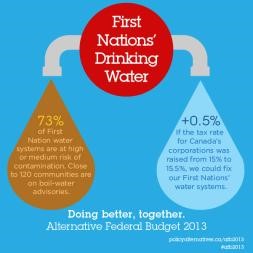

Canadians like to boast that we have the largest freshwater reserves in the world. Although we have 20% of the world’s freshwater, only 7% is renewable. Also, 73% of First Nation water “are at high or medium risk of contamination” while many of them simultaneously live alongside waterways. Why is this so?

Decolonization cannot occur without conversations about land and water. We can begin to decolonize by understanding the places that have been affected by colonialism and industrialization and these are often our waterways.

Here are a few important things to learn about the waterways you are travelling:

- Where are the source of the lakes and rivers you are paddling?

- Where do these lakes and rivers flow?

- What industries exist along the riverbanks and lakeshores?

- What communities are most negatively/positively affected by these industries?

- Who financially benefits most from these industries?

Writing about the waterways we are paddling through could take a long time. This may be a future blog post!

5. Watch Your Language

While on your paddling trip, watch your language. Canadians have internalized the history of explorers. We romanticize it. We use it in our everyday. “I discovered this awesome musician.” “I want to do [country of choice].” This is not a matter of policing language but a desire to dig deeper into why we use the language we use. These expressions are problematic because they may assume that we are the first or they can be subtly aggressive even if we did not intend to. Can we not just travel to India? Is it really an adventure to “done?” Don’t thousands of people already listen to that musician?

It is this barely noticeable mindset and language that devalued those that occupied this territory before European ancestors arrived. It is this mindset that allowed settlers to ignore how their actions affected those who lived in the areas that they were moving into. It is this mindset that allows us to also use the land as solely a commodity. So, as you paddle and see new sights and enjoy the beauty of the landscapes that you are paddling through, recognize that you are not the only one that has been there before. You are part of a long history and larger story of people living in this land. It is also important to be aware of respectful customs. For example, it is not appropriate to take photographs of pictographs. These can be found throughout Quetico Provincial Park. As you are expected to not photograph other sacred spaces and items in other faith traditions, it is also important (in a similar but not identical way) to not photograph Indigenous pictographs. Your paddling trip is not an experience to consume. It is an opportunity to continue to learn about the country that we live in and start to decolonize our thinking about it! What an exciting thing to engage in!

I hope you can take these ideas to heart before you begin your next trip whether it be a two-day or ten. Happy paddling!