The Moose Cree First Nation Hopes To Finally Work with the Ontario Government on Conservation of Watershed

This article was shared by the National Observer on October 25, 2021.

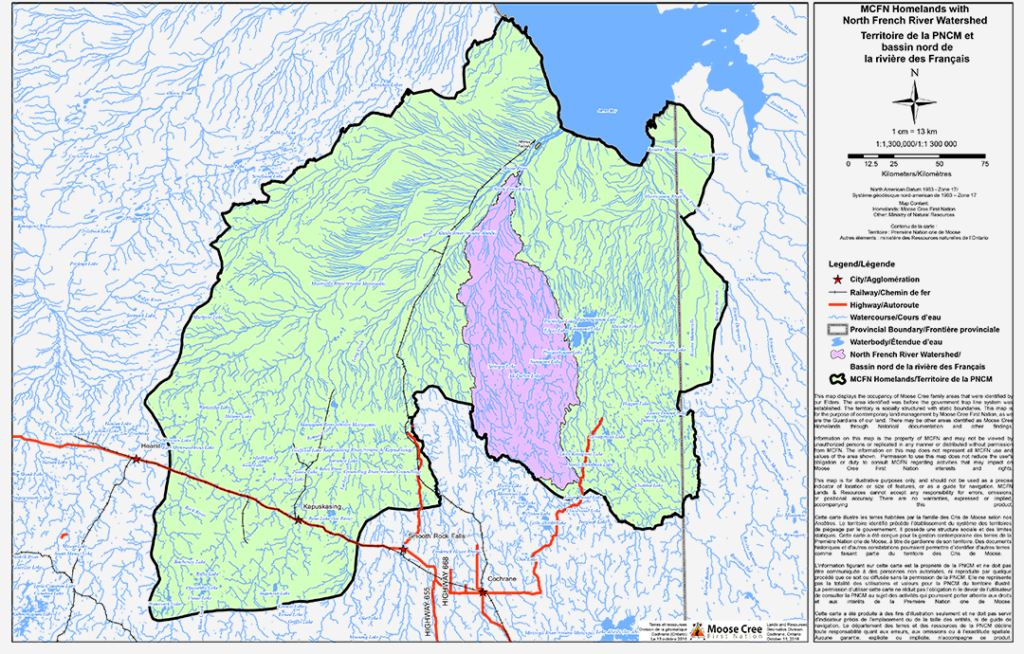

The North French River watershed, nine hours north of Toronto, sits on the traditional territory of the Moose Cree First Nation, which for decades has been striving to protect the area from further development. The nation’s past efforts were rebuffed by successive Ontario provincial governments. Now the Moose Cree must work with the Doug Ford administration, whose environmental track record includes stripping away environmental oversight, opening Algonquin Park to logging and allowing resource extraction in wilderness areas, according to an Ontario auditor general report.

But there is renewed hope for the watershed: talks are now underway to designate the area as an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) to preserve the Moose Cree First Nation’s water, land and cultural traditions from all-pervasive mining, logging, and development.

“I have to say, the provincial government has come around,” says John Turner, land use coordinator and member of the Moose Cree First Nation. “Even in light of the current government, they are willing to work with us.”

Indigenous people have long protected their areas under Indigenous laws, says Anna Baggio, conservation director at the environmental non-profit Wildlands League. For example, the Cree hand down family traplines and sections of land families rely on for sustenance, cultural practices, and hunting and trapping grounds.

But that hasn’t been enough to stave off unwanted development. The northern part of the Moose Cree territory has largely remained untouched, but the southern areas have been ravaged by industry.

Unfortunately for the Moose Cree, Ontario law is the only law practically recognized in our legal system, Baggio says. An IPCA could provide a bridge between them.

In August, the federal government announced $166 million for IPCAs as part of a push to give First Nations agency over their territories and a federal target of protecting 25 per cent of land and 25 per cent of oceans by 2025. To form an IPCA, tripartite agreements are struck between First Nations and Inuit governments and Canada’s federal and provincial government counterparts.

Until very recently, the Ontario government was the holdout thwarting the Moose Cree’s efforts to form an IPCA. The federal government was onside and gave the nation $225,000 over three years to develop a land use plan.

But Ontario was recalcitrant: the province hasn’t formally authorized an IPCA anywhere in its jurisdiction. It lags behind British Columbia, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, all of which are on board with the concept and are close to finalizing a number of IPCAs. The Northwest Territories is the front-runner: it established one of Canada’s first IPCAs in recent memory, Thaidene Nëné Territorial and Indigenous Protected Area Establishment in partnership with several First Nations.

The Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks told Canada’s National Observer the Ontario government is currently reviewing opportunities to expand and enable Indigenous-led management of protected areas. But the ministry refused to comment directly on the possibility of an IPCA for the Moose Cree First Nation.

Historically, Ontario’s reluctance illustrates a pattern of thwarting the Moose Cree’s efforts to protect their cultural traditions and determine the management of their territories for land and wildlife stewardship and natural resource management.

In 2015, the nation attempted to protect the area through its own land use plan without provincial involvement, Turner says. It failed because independent land use claims are not recognized by the province.

But more recently, the IPCA proposal has gained some traction.

Ontario and the Moose Cree are working together on the land use plan, Turner says. Half of it would govern an area of the watershed that contains no resource development; the other half covers the already developed southern parts of the watershed. An IPCA would go a long way to protecting the nation’s way of life, he adds.

“It was really bad before,” says Turner. “I’ve seen people’s livelihoods destroyed by logging companies. People have a really good, productive trapline, and you have two or three of those machines working there. The logging companies can completely clear-cut a whole trapline in a year.”

It takes 15 to 20 years, nearly a generation, for a trapline to become productive following a clear-cut, he notes.

The Moose Cree’s case for an IPCA is bolstered by the boreal forest and Hudson Bay Lowlands, which sequester more than twice the amount of carbon locked in tropical forests like the Amazon. Canada’s federal climate targets will not be met if the boreal forest continues to be disturbed by development, according to a report by the non-profit National Resources Defense Council. The forests hold more than 80 per cent of their carbon in moss. Part of the Moose Cree’s argument contends the protection of the watershed will significantly reduce carbon emissions.

But for Turner, preservation of clean water sits at the heart of the IPCA negotiations, partly because of its spiritual significance. Life requires clean water stretching for generations in the past and future, he says.