Oil Now Out of Sight, Out of Mind?

|

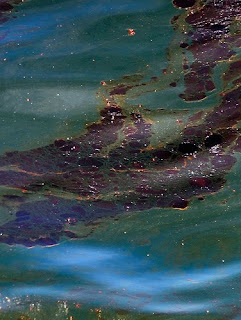

| An oil slick on the Gulf of Mexico, June 12, 2010 Photo by Deepwater Horizon Response/flickr |

After the Deepwater Horizon oil well began spewing millions of litres of oil into the Gulf of Mexico earlier this year, governments, scientists, and coastal communities braced for what was expected to be a long and arduous clean-up effort. As attempts to stop the flow of oil failed repeatedly, the spill eventually grew to become the worst ecological disaster to hit American shores. The oil recovery effort was expected to continue for a very long time.

Scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) discovered an oil plume that spanned roughly 35 kilometres in length, reached heights of 200 metres and was 2 kilometres wide. This oil plume lingers more than 900 metres below the ocean’s surface and is believed will remain for months; however the environmental repercussions will be felt for years.

Following this latest discovery, it was revealed that more oil was present at the bottom of the seafloor up to depths of over 1,200 metres. Scientists discovered that a substantial layer of oil sediments rests on the bottom of the seafloor stretching several kilometres in all directions.

Samantha Joye, a professor at the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of Georgia, set sail on August 21 to better understand where the 750 million plus litres of oil went and she now has a pretty good idea. “It’s showing up in samples of the seafloor, between the well site and the coast. I’ve collected literally hundreds of sediment cores from the Gulf of Mexico.” The oil sediments covering the seafloor are about two inches thick and in some samples they found tar balls, dead shrimp, worms and other invertebrates.

It’s widely accepted that it will take months if not years before scientists are able to produce a true picture of the effects of the BP spill. In the meantime, we need to ensure that this type of tragedy is not repeated in Canada. Take action now and send a letter to the Canadian government to place a temporary moratorium on new off-shore drilling projects as was done in the U.S. immediately following the Gulf of Mexico disaster.