No Bull: Native Trout Threatened in Alberta

The bull trout (salvelinus confluentus) is a salmonid, specifically a char, and Alberta’s official provincial fish. Native to northwestern North America, bull trout of Alberta are listed as a threatened species according to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and as a vulnerable species under the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. A recent Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development blog post estimates that there are only a total of approximately 20, 000 bull trout remaining in the province. That population estimate alone might not set off alarm bells to the casual reader, but when you consider that the Alberta Government’s fish stocking program planted 1, 667, 406 rainbow, brown, and brook trout (or roughly 83 times the total number of native bull trout) into local water bodies in 2014 alone, the significance of the estimate is infinitely more apparent.

According to the Alberta’s Species at Risk Program “Bull Trout Conservation Management Plan 2012 – 2017,” bull trout have suffered a 33% reduction in historical range and 78% of the identified core management areas are vulnerable to extirpation, with 6% already considered extirpated. The report also states that where bull trout recovery has occurred, it has been mostly due to angling regulation changes such as the province-wide zero retention limit and localized bait bans. This leaves the province’s highly active resource extraction and development industries as the most substantial hurdle to bull trout survival and recovery.

Bull trout can be distinguished from other char by the lack of dark markings on the dorsal fin (as appears in the non-native brook trout), or the lack of a deeply forked tail (as found in Alberta’s only other native char—the lake trout). Bull trout tend to be a dark grey to olive in colour, with yellow to red coloured spots, white leading edges on their fins, and a large head in proportion to their bodies when compared to other salmonid species.

Bull trout can be distinguished from other char by the lack of dark markings on the dorsal fin (as appears in the non-native brook trout), or the lack of a deeply forked tail (as found in Alberta’s only other native char—the lake trout). Bull trout tend to be a dark grey to olive in colour, with yellow to red coloured spots, white leading edges on their fins, and a large head in proportion to their bodies when compared to other salmonid species.

There are two main variations of the bull trout. “Resident” bull trout are the smaller of the two and remain in the same stream for their entire lives. “Migratory” bull trout, on the other hand, move throughout watersheds, lakes, and the ocean in coastal populations. Migratory bull trout tend to get much larger than resident bull trout and can achieve weights of over 10kg, while resident bull trout rarely reach half of that size.

Bull trout are slow to mature and have exacting habitat demands, especially when spawning, and this has led to a number of complications leading to their decline in recent years. Competition from non-native brook trout threatens populations in many river systems, with hybridization being a major concern, and pressure from native lake trout has proved to all but completely displace bull trout in circumstances where they are forced to compete, such as the creation of Abraham Lake with the construction of the Bighorn Dam on the North Saskatchewan River in the 1970s. The increased warming and sedimentation of the headwaters spawning areas of bull trout due to logging, oil and gas exploration, and recreation use has also played a significant role the decline of the bull trout.

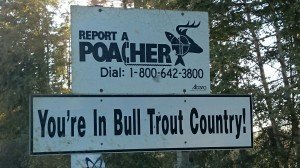

The outlook isn’t all bad for the bull trout, however. The recent official designation as a threatened species will hopefully usher in some changes in protection and management of its fragile aquatic territories. Recent regional plans have also acknowledged that increased recreational education and enforcement is necessary to stop the degradation of important habitat. As is so often the case, the bull trout is another example of the conflict between economic and ecological concerns and, hopefully, future changes to headwaters management will provide some protection to this amazing fish. Living in the coldest, cleanest, and clearest waters, bull trout are an integral indicator species of fresh water quality. They are worth protecting. For, as stated in The Fishes of Middle and North America published in 1896, “no higher praise can be given to a Salmonid than, to say it is a charr.”

The outlook isn’t all bad for the bull trout, however. The recent official designation as a threatened species will hopefully usher in some changes in protection and management of its fragile aquatic territories. Recent regional plans have also acknowledged that increased recreational education and enforcement is necessary to stop the degradation of important habitat. As is so often the case, the bull trout is another example of the conflict between economic and ecological concerns and, hopefully, future changes to headwaters management will provide some protection to this amazing fish. Living in the coldest, cleanest, and clearest waters, bull trout are an integral indicator species of fresh water quality. They are worth protecting. For, as stated in The Fishes of Middle and North America published in 1896, “no higher praise can be given to a Salmonid than, to say it is a charr.”

Cory Willard has a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Calgary and an M.A. in English Rhetoric and Communication Design from the University of Waterloo. He is an avid fly fisher and outdoorsmen and is particularly interested in how outdoor activities can physically and spiritually bond people to places and turn them into ecologically aware environmental defenders.

You can connect with Cory on his blog http://corywillard.wordpress.com or via twitter @_cgwillard